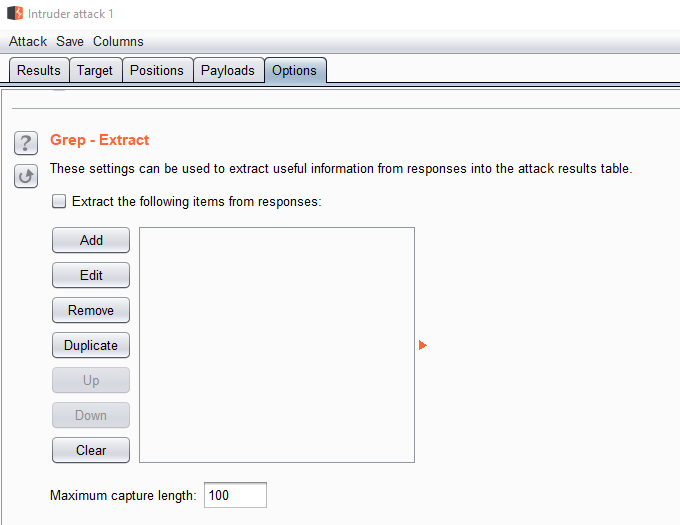

Burp Suite’s “Intruder” is one of my favourite features. It automates various parts of my job for me by repeating a baseline request with minor variations. You can then check out how a target responded. Unlike the “Reapeater” you get a nice table of results and at a glance can find things with different response codes. Basically Intruder is brilliant.

Intruder has a feature called Grep Extract which allows you to find content within HTTP Responses and then extract the values. You might want to do this if you are enumerating users by an ID and you want to extract the email addresses for example.

I looked but could not find the same functionality via the Proxy History so I made a simple Extender to add that functionality. This blog post covers:

- Basic Usage of Grep Extract – showing how to use Grep Extract within Intruder. Why not show the inspiration?

- Grep Extractor – showing the code and how to use it.

This extender is designed to have the code altered by you when you want to extract something. It has never been easier for you to get your hands dirty and get a new Extender that does something useful!

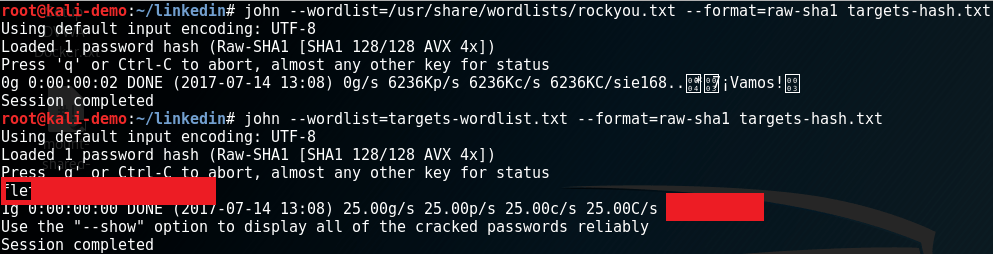

Basic Usage of Grep Extract

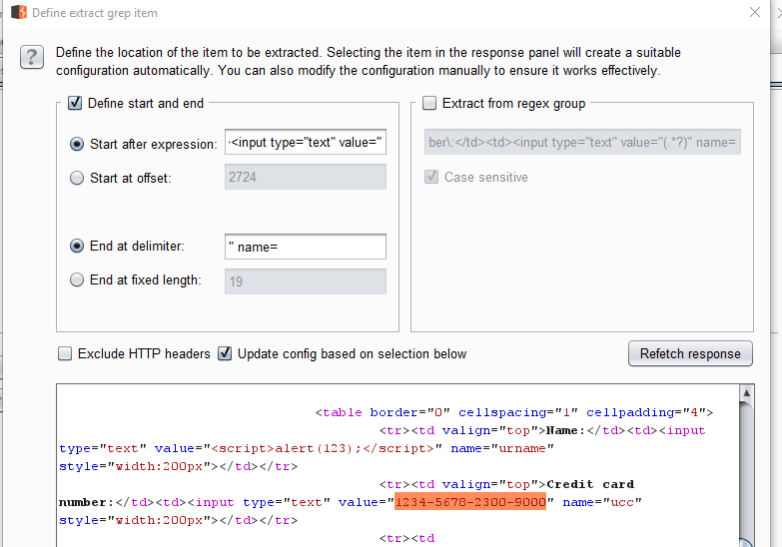

When you are inspecting the results of an intruder attack you can use the “options” tab and “Grep – Extract” down at the bottom to extract data from a response. Here is what the options look like:

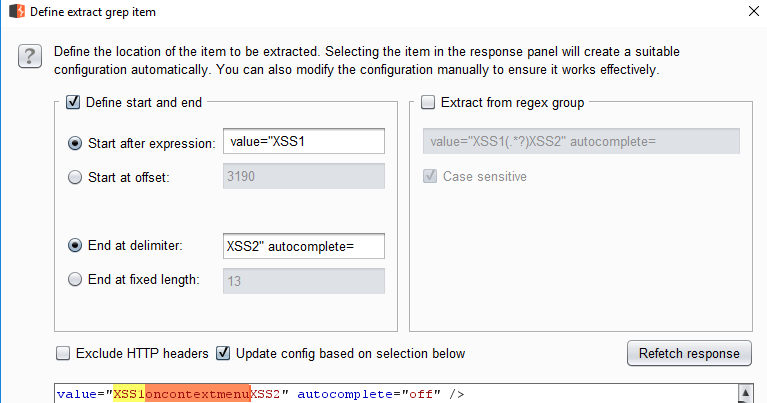

Click on “Add” to bring up the screen below where you can simply highlight the part you want to extract:

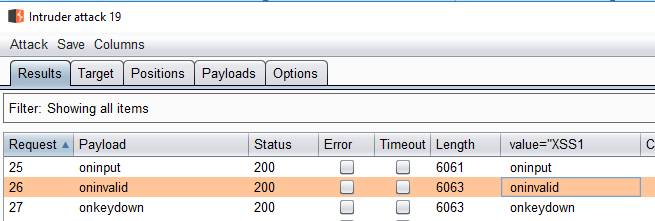

In this case the response page has a Credit Card number so I highlighted that part. When you apply that the Intruder results table will update to include a new column with the extracted data:

You can export the results to a CSV file via that “Save” menu. This is all very well and good when you are using Intruder.

Grep Extractor

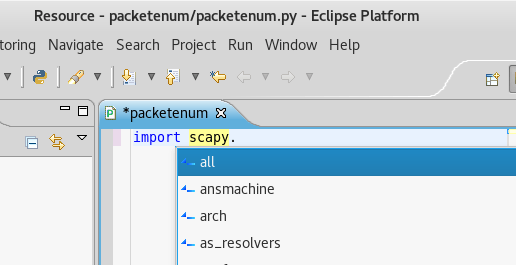

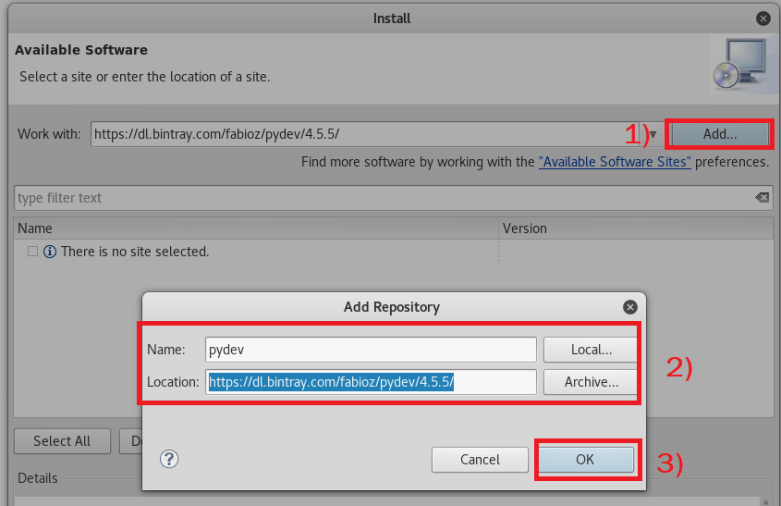

You have seen how Burp provides this feature within Intruder. It uses a nice GUI approach which we are not replicating at all. The following shows the source code for Grep Extractor:

#burp imports

from burp import IBurpExtender

from burp import IBurpExtenderCallbacks

from burp import IExtensionHelpers

from burp import IContextMenuFactory

from burp import IContextMenuInvocation

import re

# java imports

from javax.swing import JMenuItem

import threading

class BurpExtender(IBurpExtender, IContextMenuFactory):

def registerExtenderCallbacks(self, callbacks):

self.callbacks = callbacks

self.helpers = callbacks.getHelpers()

self.callbacks.setExtensionName("Grep Extractor")

self.callbacks.registerContextMenuFactory(self)

return

def createMenuItems(self, invocation):

menu_list = []

menu_list.append(JMenuItem("Grep Extractor", None, actionPerformed= lambda x, inv=invocation:self.startThreaded(self.grep_extract,inv)))

return menu_list

def startThreaded(self, func, *args):

th = threading.Thread(target=func,args=args)

th.start()

def grep_extract(self, invocation):

http_traffic = invocation.getSelectedMessages()

count = 0

for traffic in http_traffic:

count = count + 1

if traffic.getResponse() != None:

# if the string is in the request or response

req = traffic.getRequest().tostring()

res = traffic.getResponse().tostring()

# start is the string immediately before the bit you want to extract

# end is the string immediately after the bit you want to extract

start = ""

end = ""

# example parsing response. Change res to req if data is in request.

i = 0

for line in res.split('\n'):

if start in line:

# extract the string

extracted = line[line.find(start)+len(start):]

extracted = extracted [0:extracted .find(end)]

# print exracted string, visible in Burp

print extracted

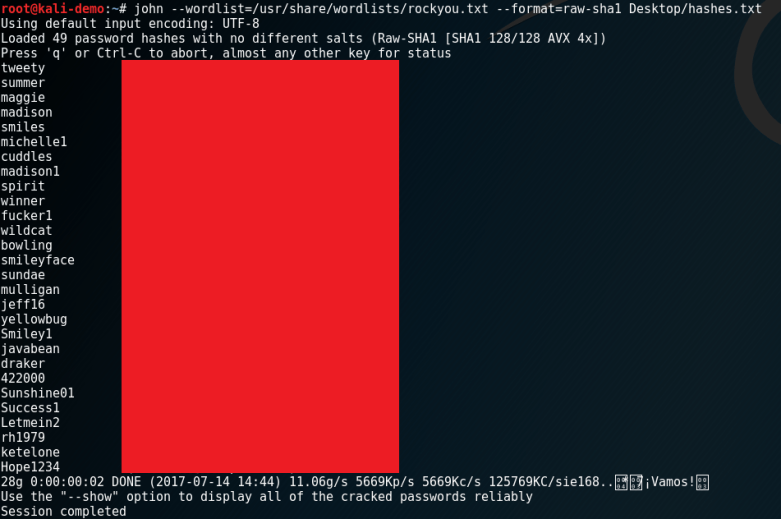

Nothing too scary in there and the comments should help you out. Lets give one simple example of how to use it. Lets say the site you are targeting has the “X-Powered-By” header. Was that consistent across all responses or did it alter at any point? Perhaps some folder is redirecting to a different backend system and you didn’t notice.

Modify the start and end strings as shown below:

start = "X-Powered-By:" end = "\n"

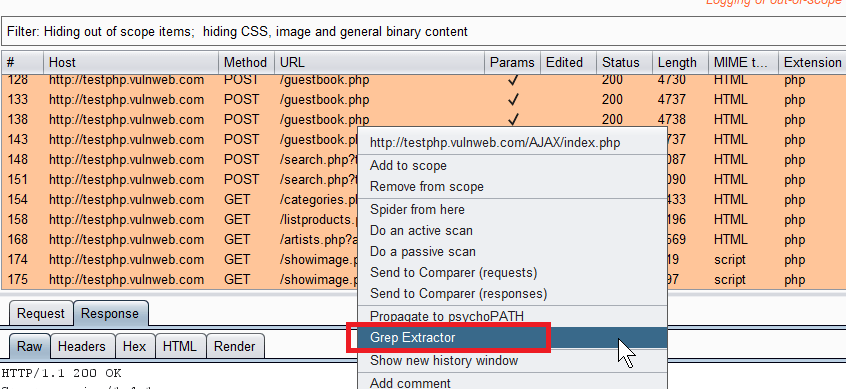

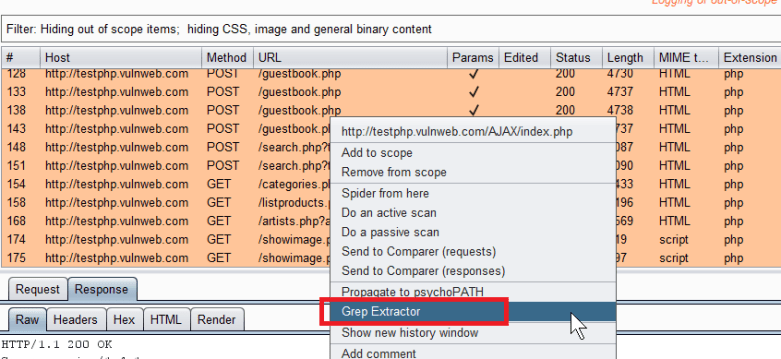

Any data between “X-Powered-By:” and the next newline character will be printed out. Save your code and then reload the Extender within Burp. At this point you can right click on one or more entries in the proxy history and send to Grep Extractor via the option shown below:

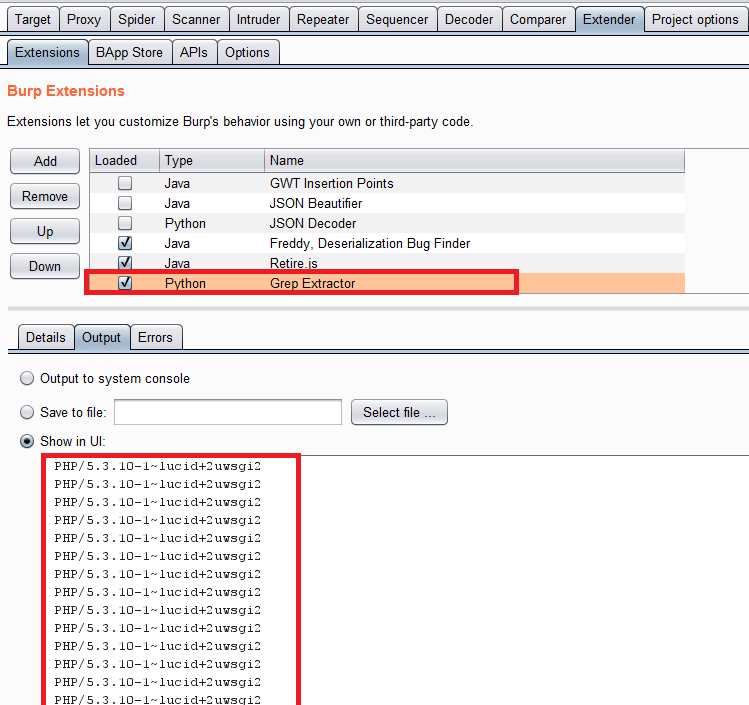

Any “print” commands issued from the Extender will goto the output for the extender. This is visible on the following menu:

Extender -> Select “Grep Extractor” -> Select “Output” tab.

The following shows output from the proxy history with our target:

It looks like the target site is consistent with it’s “X-Powered-By” headers. Well we struck out there but hopefully you can see the benefits of getting dirty and dipping your toes in the ocean of Burp Extenders. With relatively little coding knowledge you can get powerful results from Grep Extractor.

Example X-CSRF-Token

This example shows how to markup each request which did NOT include the HTTP header “X-CSRF-Token”:

def grep_extract(self, invocation):

http_traffic = invocation.getSelectedMessages()

count = 0

for traffic in http_traffic:

count = count + 1

if traffic.getResponse() != None:

# if the string is in the request or response

req = traffic.getRequest().tostring()

if req.find("X-CSRF-Token:")== -1:

traffic.setComment("Request without X-CSRF-Token header")

traffic.setHighlight("pink")

This uses the “setComment” and “setHighlight” methods as documented at the following URL:

https://portswigger.net/burp/extender/api/burp/IHttpRequestResponse.html

Instead of logging information to the stdout this will update all requests within proxy visibly with a pink background and a useful comment. This does not alter any pre-existing highlights or comments (at least when I tested it).

By reviewing the proxy history I discovered the token was consistently set for everything apart from the login form. There was no impact but it helped me get to this answer quickly.

Example Set-Cookie

This example shows how to print out every “Set-Cookie” directive in the selected responses:

def grep_extract(self, invocation):

http_traffic = invocation.getSelectedMessages()

count = 0

for traffic in http_traffic:

count = count + 1

if traffic.getResponse() != None:

# if the string is in the request or response

req = traffic.getRequest().tostring()

res = traffic.getResponse().tostring()

start = "Set-Cookie:"

end = "\n"

for line in res.split("\n"):

if line.find(start) !=-1:

line = line.strip()

print line

I needed to do this when conducting a re-test of an application which had certain cookies set without “httpOnly” and others without “secure” flags. By printing the full “Set-Cookie” directive I even visually caught a few anomalies where rare cases resulted in “secure; secure;”. Most likely the result of the framework and then reverse proxy ensuring the flag was set. It only affected one folder.

Vulnerable Test Site

The data shown in the proxy logs all comes from browsing the vulnerable website from Acunetix available below:

This was just to populate my Burp history with a few requests and responses.

Hope that helps,

Cornerpirate