Recently I found myself up against CloudFlare. I was able to sidestep it during the engagement and then get SQLMap working.

If you are short on time here is the technique in a nutshell:

- Find the IP address for the backend server. You can try securitytrails.com, or brute force against a list of IP addresses using CloudSniffer.

- Confirm that you can access the HTTP/HTTPs services on the backend service:

nmap -sS -sV -p 80,443 <target_ip>- Visit it by the IP address and overwrite the “Host:” header with the target hostname. You can also probably get there by editing your /etc/hosts file properly.

I hope that gets you where you needed to go. If you have the time, then context is often entertaining.

Why, how and narrative

I was testing a customer’s website with access to the source code. Running it through VisualCodeGrepper reported thousands of probable SQL Injection vulnerabilities. Customer also gave me last years Pentest Report (from another provider) which did not mention any injection style issues. This seemed like a fairly big miss.

Burp Suite had no problems detecting an injection point based only on supplying a single-quote versus supplying two. This was the first URL I scanned on day one of the test. The site is completely riddled with SQL Injection. We are testing in production. Oh no.

Manual investigation found no error for “ORDER BY 5 — “, but a 500 error on “ORDER BY 6 — “. SQL Injection fans would then know the next step is “UNION SELECT null,null,null,null.null — “.

Here is where CloudFlare kicked into the story. It seemed to dislike “UNION” pretty hard. Trying various encoding and regex busting techniques such as comments failed to get around this.

This blog post is not describing a zero day in some WAF rule that I cleverly bypassed with some novel approach.

Web Application Pentesting 101

This is a penetration test. We are working in collaboration with the customer. The goal is to find and provide recommendations to fix as many issues as possible. For that reason our pre-requisites ask that WAFs are disabled from our source IP addresses precisely so we are not wasting our time being dropped by a WAF.

If you want us to confirm that your WAF is protecting you first disable it for us so we can land grab as many vulnerabilities as possible. Then turn it back on so we can confirm which were still exploitable.

No you do not want to waste your time doing it with the WAF on first. A penetration test is not a scenario based engagement like red teaming. If you want the test to occur with the defences fully in place well…. You will need to make the duration longer than you probably want to pay for and there is still no guarantees that it will be as useful as the recommended approach.

Back to Bypassing CloudFlare

Without finding a regex busting bypass for “UNION” (and various other SQL function names) what can you do? If the deployment of CloudFlare has failed to sandbox the original backend server then you can completely bypass it. The process is this simple:

- Find the backend IP address.

- Edit the /etc/hosts file to map that; or

- Access the target by IP address and ensure that the “Host:” request header is properly set.

Points 2 and 3 are achieving the same results really. Making sure that your computer goes straight to the original backend IP instead of using DNS to find the intended CloudFlare fronted interface you would usually get.

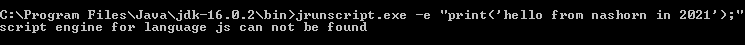

Find the backend IP address using securitytrails.com

I signed up for a free account on securitytrails.com. I put the target hostname in and then selected “historical data”. I cannot give you the data for the customer obviously but I can show you the historical data for cornerpirate.com:

The important parts here are that it shows you the organisation, and the “last seen” and “duration seen”.

The customer’s site suddenly had the organisation set to “CloudFlare” 7 months prior to the test. For the previous decade the device was hosted on an IP address that they own. I took a wild guess that the original IP had not been altered.

Before proceeding you need to confirm that the original IP address is offering ports 80, 443 or whatever the target is running on. To do that simply use nmap:

nmap -sS -sV -p 80,443 <target_ip>

If the port you want is “open” then you are very likely in.

Find the IP address using CloudSniffer

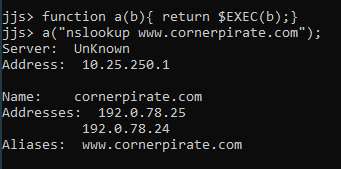

SecurityTrails.com worked well for me. But what if your target has no history, or you just really don’t want to sign up for a free account? Well you can use CloudSniffer to do it the hard way. This is able to take a text file of IP addresses and then it will scan them to see if they respond identically to the target host you also provide it:

python CloudSniffer.py <target_domain> <ips_in_file> --cleandns

To find the IP addresses you should do some OSINT on the organisation to find netblocks they own.

Using your new bestest IP with SQLMap

If you can remember the narrative here we were trying to bypass CloudFlare to allow us to exploit SQL Injection. You can confirm that CloudFlare is no longer an issue by repeating the request you made with the “UNION SELECT null,null,null,null.null — “. If this now works and you get no error (for an appropriately formatted payload) then you are free to fire SQLMap at it now.

What I did was save the baseline request into “req1.txt” and then used SQLMap’s -r to load that. To be extra sure DNS was not going to kick in I modified the “Host: ” header in “req1.txt” to point to the IP address. This would allow SQLMap to find the target by the IP address.

Since HTTP 1.1 requests need the correct “Host: ” header to be set otherwise you won’t be given the application you desire. Use the –headers=”Host: <target_hostname>” so you can force the correct header:

sqlmap -r req1.txt --headers="Host: <target_hostname>"

It then found the injection point and I went about my way.

The few blog posts I read about this CloudFlare Bypass technique missed the next hop out where you use the IP. Probably because it is obvious right? But I felt it was important to show the SQLMap step I used.

But, there are many ways to skin that goose for various scenarios:

- Modify your /etc/hosts file appropriately.

- In Burp 1 – set up a custom DNS rule so it resolves to the IP

- In Burp 2 – target the site by IP address in your browser and use a match/replace rule to set the Host header correctly.

Hope this helps